Global Partnerships and Saving the Giraffe

September 30, 2018 - 9 minutes read

David O’Connor

The San Diego Zoo’s Global Partnerships program connects animal care, conservation research and education experts with regional, national, and international agencies, zoos, benefactors, and conservation NGOs in collaborative efforts to end extinction.

Born and raised in Ireland but now a long-time resident of San Diego, community based conservation ecologist David O’Connor spearheads the program’s partnerships in Kenya, including projects at the Loisaba and Lewa wildlife conservancies — where The Elewana Collection offers luxury safari camps — to research and figure out better ways to ensure the survival of giraffes, leopards and six other species.

O’Connor recently sat for a chat with Emerging Destinations. Here’s part two of that interview:

ED: How does the Global Partnerships work at Lewa Conservancy differ from what you’re doing at Loisaba?

DO: Lewa has been around and active in conservation longer and they are excellent at what they are doing — with rhinos in particular. They have a lot of partners already who are supporting them. So the primary work that we do at Lewa has been assisting with program evaluation so they can have a metric of success for feedback to donors over time, as well as supporting some of their conservation research programs.

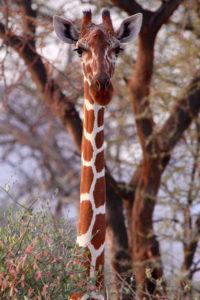

We work a lot with their conservation education team. We do an annual giraffe count where we photograph and ID all their giraffe so they can, over time, see the change in their population because it’s fenced and we can see immigration and emigration patterns. We can identify individual giraffe by their coat pattern.

Along with KWS [Kenya Wildlife Service] we are building a diagnostic lab for vets there. Because now in northern Kenya — when they take samples of suspected wildlife disease be it Rift Valley fever, foot and mouth, anthrax, etc — it’s hard to get those samples analyzed because they sometimes have to go to Nairobi. And trying to get anthrax to Nairobi can be tricky.

One of your biggest and most important projects in Kenya revolve around the giraffe. What have  you learned about them so far?

you learned about them so far?

Generally speaking, we know very little about giraffe compared to other iconic species. What I find particularly interesting about the giraffe is that it’s uniquely African. Elephants you find elsewhere, lions you find elsewhere, leopards you find elsewhere, cheetah you find elsewhere. But giraffe are uniquely African, you only find it in Africa. And we know so little about it. But we do know the population is declining. The estimates are pretty bad in terms of overall drop — a 40 percent decline in the past 30 years.

In Africa as a whole?

Yes. Based on the IUCN assessment in December 2016 that got them listed from least concern to vulnerable, which is the same classification as African elephants, lion and cheetah. Underscoring how little we know about giraffe is that we don’t know how many species or subspecies there actually are. The current thought is one species with between nine and 11 subspecies.

However — lead by the Giraffe Conservation Foundation — we have found enough genetic evidence to show that, genetically speaking, there are four different full species of giraffe. Each as different from each other genetic-wise as polar bears to brown bears. And the reticulated giraffe is its own species. The reticulated giraffe, based on the ICUN estimate, has declined between 50 and 70 percent in the past 30 years. The reasons for that are unclear, but likely to climate chaos, land degradation and poaching to a certain degree.

People poach giraffes?

Yes. For meat primarily, and for parts. Some of the parts are valuable. We are doing a study now to understand the trade in giraffe meat and other parts. We just started that this summer with the NRT [Northern Rangeland Trust]. For instance, when it come to Samburu, giraffe is their favorite of all the wild meat they eat.

Those were the drivers behind Global wanting to focus on the reticulated giraffe. What we are doing in Loisaba and Lewa is trying to understand the spatial dynamics of the giraffe in terms of what type of habitat are they occupying at different times of year and trying to understand why they are occupying these types of habitat. Why do they abandon this area at this time of year? We don’t know why. We just have educated guesses.

We also have a big collaring program with attaching satellite tracking units to giraffe as part of a continent-wide effort to collar up to 250 giraffe across Africa in the next five years. From that we want to know giraffe range, what type of habitat, how long they spend in each habitat. Once we know that, it can really help inform conservation decision making efforts.

San Diego Zoo Global

So the project also includes interaction with local residents?

The human dimension is a big part of what we’re doing. We talk to a lot of people in the surrounding communities about how they feel about giraffes, whether they feel that they bring benefits like tourism, is there any conflict with giraffe, their rate of meat consumption. Whether they eat the meat or hear or see poaching.

The last piece that we are looking at is giraffe movement in relation to livestock. So in addition to collaring giraffe, we are collaring livestock. We’ve already started the pilot project in Loisaba. Some of the herds up there have a collar on them so we are tracking the movement of community cattle and camels to see how they move in relation to giraffe. One of the findings we have found from the collared giraffe already is that Loisaba is not big enough to support giraffe. The collard giraffe have pretty much all left the reserve. They come back sometimes but their range is much greater than what Loisaba alone can support.

Do you have any idea how big infrastructure projects in northern Kenya — like the massive Lake Turkana Wind Power Project — are going to impact giraffe and other species in the region?

We don’t know how that’s going to interrupt giraffe movement patterns — because we don’t know giraffe movement patterns. Maybe they move a lot, maybe they move a little. We do know the movement patterns for elephants. They have fantastic data that shows exactly where the elephants cross this road. Maybe they can build an underpass and maybe they can build an overpass — the kind of things that can minimize the impact of these infrastructure that, of course, any developing nation wants. Those are the kinds of questions that we are asking.

0 Comments